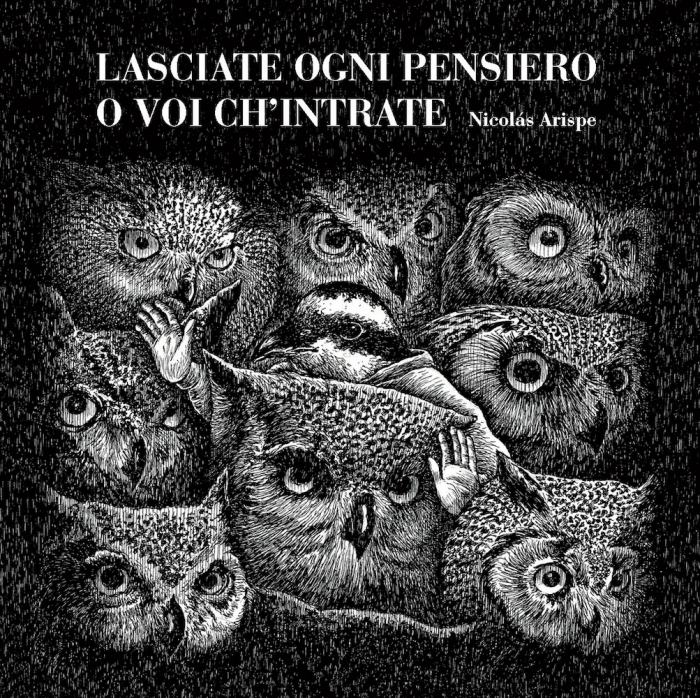

Let’s start from the title, which translates as “All thoughts abandon ye who enter here”. This sentence was written once on the Orcus mouth in the Gardens of Bomarzo (where nowadays we can read “Ogni pensiero vola”, “All Thoughts Fly”). Why did you choose this sentence, what does it mean to you and to this book in particular? How did you end up drawing inspiration from the Gardens of Bomarzo?

N: The book is about a dream: everything that happens, happens in the protagonist’s dream. The story itself is a dream (a nightmare, to be precise).

The title invites us to leave all thoughts behind and enter the world of dreams, a world lying outside the field of reason, of thought, of awareness (“The sleep of reason produces monsters” as Goya would put it).

But there is something more in this sentence: it is an order. We cannot choose how to enter this territory, nor can we choose not to dream. Everything that happens to the protagonist of the book is irrational and, in a sense, surreal. Logical thinking is left behind.

As for the Orcus of the Gardens of Bomarzo, it entered the book because on the one hand it gave me this idea and this sentence (of course quoting Dante), and on the other hand many of the scenes in the book have to do with dreamlike, bizarre, surreal works (see the references to De Chirico, Goya, medieval witchcraft treatises etc.).

I am also obsessed with Italian Mannerism: I believe that Mannerism as a style always represents a breakthrough in the approach to representation, which implies a change in the established standards. I already quoted it in the past, for example in La madre e la morte/La perdita (The Mother and the Death/The Loss) where you can see the Buontalenti grotto, in the scene where the mother crosses the mountain.

I have been studying the Gardens by Pirro Ligorio for years, with the aim of doing something with it, sooner or later. In this book I had the possibility to include the Orcus, which is maybe the most famous of his monsters.

As a matter of curiosity, the Gardens of Bomarzo were at the centre of a debate in Argentinian history: a good author, though a little forgotten, Manuel Mujica Lainez, wrote a novel titled Bomarzo. It deals with the life of Count Orsini, written after Mujica Lainez’s visit to the Gardens, which left a deep impression on him.

[Composer] Alberto Ginastera turned the book into a lyrical opera of the same name, which was performed for the first time in Washington DC in 1967, causing a public outcry to the point that censorship forbade its subsequent staging in Buenos Aires (Argentina was under a military dictatorship at the time).

Though very different from each other, your last books (La madre e la morte/La perdita and Il libro sacro) had a narrative structure. This one looks more like a sequence of scenes, a journey whose fil rouge is the bird-woman escaping. Where did you get the idea for the book, and what was its genesis?

N: The book follows a path, namely the constant escape of the bird-woman, that I chose to represent according to the traditional scheme of introduction-development-conclusion. It is true, however, that the only connection from one scene to another is the presence of the bird-woman. They are not ‘rationally’ connected. The mechanism is always the same: the bird-woman, trying to escape a negative situation, gets stuck in the next one.

I was inspired by a painting by Jean-François Millet, Peasant Girls with Brushwood. At first, I wanted to illustrate the nightmares of these people forced into hard labour.

Then I ended up reversing the point of view and the labour of those women turned into someone else’s nightmare. That’s when the bird character showed up. The concept in itself is easy: the appalling nightmare of the bird-woman is made of all the troubles of our daily life. The bird fills up its nightmare with our everyday life (alienation as she is thrown out of culture, the social stigma experienced by women charged with witchcraft, the fear of death, the imprisonment–represented by the reclusion inside the Orcus–, the sense of dread when faced with nature’s most uncontrollable aspects, as in the bird-woman’s fall into the depths of the sea).

Of course all this is told through metaphors: it’s the context of the nightmare itself that allows us to do it.

Why did you decide to tell this story without words? Have you tried to write a text at a certain point or has it been a silent book since the beginning?

N: In my last two books I changed the way I work. In the past, I used to write first, and then I started to draw. In the last book published before Lasciate ogni pensiero… I reversed the process: I first drew the whole story, then I wrote the texts. And now I have gone ever further, and decided to completely leave out words. I did some sketches, I designed the scenes and the subject, then I started to draw.

There were moments when I thought I could add a text. But then, after some attempts, I felt that words were not adding anything, and that the story could even flow better without them. I believe that in a sense silence, which of course is a resource of the text–just like it happens with music–gives the story a greater dramatic tension and a sense of dizziness.

The protagonist is a zoomorphic being, as in some of your past books. Could you explain us why this theme fascinates you so deeply? And, in this last book, why did you choose a bird, and what kind of bird is it?

N: On the one hand, animals have always been the protagonists of many fables, a literary genre I am interested in because it raises moral issues quite directly.

On the other hand, in the history of images animals belong to a tradition in which they embody given stereotypes: donkeys are dumb, pigs are voracious, lions are majestic, crows are deceiving, foxes are smart and nasty etc.

I am fascinated by these stereotypes, which are the outcome of thoughts and prejudices lying behind cultural production.

As far as I am concerned, I try to make use of these stereotypes sometimes in a positive, sometimes in a negative way, according to what I want to tell.

In La madre e la morte, for example, the mother is a fox, as Jonah in Il libro sacro. However, both are all but cunning. They are intelligent, of course: I wanted to refute the idea that intelligence goes hand in hand with a certain malice.

The bird-woman is represented by a bird that in Argentina is called Benteveo común. It is a common species, thousands of these birds populate both the cities and the countries, and people who love to sleep hate them, as they start singing very early in the morning.

To me, in a sense, they represent crowds, ordinary people. Mixed with one of Millet’s peasants they embody a working-class, popular character.

Furthermore, of course, birds are immediately associated with the idea of flight, of freedom, something that adds tension to the character of the chained peasant.

As we have already pointed out, the book consists of a sequence of scenes, each including a reference to the world of art, cinema, history (De Chirico, medieval bestiaries and witchcraft treatises, Bergman, Grünewald, Malevič, Millet). These references, however, do not follow a chronological nor–apparently–a logical progression. Which actually happens in dreams. How did you choose these references? Are they the cornerstones of your œuvre, which you decided to collect in a book? Or did they flow one after another as you were working on this project?

N: You’re right, all these references do no follow a particular–logical or chronological–order. Lately I approached the works of Georges Didi-Huberman, who stated that to be in front of an image means to be in front of time itself. He believes that images are stored in our collective memory and our unconsciousness, and they cyclically come back through the history of cultures according to the evolution of communities. I am also interested in the use of these images as an act of profanation, as Giorgio Agamben puts it: to take them away from their sacred places in order to disarm them, rethink them and give them a new meaning.

Therefore I like to read these images in two different ways: as mysteries (namely, as a synthesis of given social and cultural phenomena like witches, animals, death, the devil etc.) and as tools for thought (the condition of women in different historical periods, that of workers–as for example of the peasant girl–or the representation of the unknown–as in medieval bestiaries etc.). The reason why I work with these references is that I believe each of them recalls something that readers already have in their minds, something in which they can see themselves (or with which they can collide).

Now let’s talk about your technique. Can you tell us how you work?

N: My technique is really simple, I only use three tools: a 0,5 mm mechanical pencil with hard graphite, an eraser and a 0,2 mm Rotring pen.

I always use the same sheets of paper: rough Fabriano 160 g/m2.

I always design each page as a series of small pictures.

I also do a lot of research: I collect images, movies, texts, I write diary notes etc., all somehow linked to my projects. This hoard of information is a kind of enormous pot from which I develop the final images.

I first draw with graphite on sheets (which are in their final size and format), then I trace it all over with the pen.

I basically work with textures and hatchings, and I care a lot about composition, which is all about the balance and the dynamics of each image depending on its content.

The first thing I do when I trace over the images with the pen is–with the white paper as a reference point–to apply the darkest tone I intend to use. This helps me define the range of lights and shadows I am going to use in every image. I recently posted some images on my Facebook page that show exactly this process.

In the last images, the bird-woman meets a giant version of herself working as a slave in a field. Our protagonist frees her, but the devil that keeps her in chains avenges himself by surrounding her with a whirlwind of disquieting, threatening characters. In the following images, the bird, which is not wearing human clothes any longer, wakes up in its nest. A doubt remains, however: who won? The oppressor or the unruly bird-woman?

N: Well… this is difficult to say… It depends on the reader …

The dream was the bird’s. We might say that, by waking up, it breaks free because the nightmare is over.

But we should keep in mind that the bird-woman’s nightmare is actually made of some of the most awful aspects of our reality and our history.

In this case, are we able to defeat what troubles us when we are awake?

Maybe, contrary to what happens to the bird, we manage to do it in our dreams… or maybe not?

Nicolás Arispe was born in 1978 in Buenos Aires and studied at the Instituto Universitario Nacional del Arte (IUNA). As an artist, he has worked for a few magazines and fanzines and has made CD covers and storyboards for animation movies. As an illustrator he has worked with several international publishers and his comic strips have been published on several magazines, including Suda Mery K!. He is also a teacher. His books for #logosedizioni are: La madre e la morte / La perdita, Il libro sacro.

LASCIATE OGNI PENSIERO O VOI CH’INTRATE

Nicolás Arispe

#logosedizioni

hardcover, 40 pages, 220x220 mm

ISBN: 9788857609973