About our life

During a meeting organized by Taschen in Cologne, Sebastião and Lélia’s sincere words moved me close to tears: their enriching experience should be shared with everyone, so here it is the transcription.

Sebastião: When I frame a shot, when I become part of the flow that guides me to a good picture, I get really excited. But I should speak of another important element: these photographs are something more than just a bunch of nice pictures, these photographs are a way of life, our way of life (he looks at his wife Lélia and takes her hand). When we arrived in Europe at the end of the 60s, I wanted to take a PhD in economics in France, while Lélia was pursuing her studies as an architect in Paris. We had left our country because it was impossible to stay there for us, since we took part in the leftist movement, which encouraged the fight against the Brazilian dictatorship. We came to France to start from scratch. At the same time, we continued to study Marxism, dialectical materialism, geopolitics and anthropology, because France had just experienced the events of May 1968 and the whole continent was extremely politicized. At the end of the Sixties, there was such a strong movement spreading in Brazil, the whole Latin America and Europe. And in France we saw it materialize before our eyes; it was important for us. After finishing my studies and taking my PhD in economics, I went to London to work as an economist and I discovered photography through a camera that Lélia had brought to take pictures of the architecture there. Photography invaded my life, ultimately our life, and together we decided that I should stop working as an economist and become a photographer. We were taking a risk because I simply loved photography but had no idea what kind of photographer I was – an ordinary, an average or a real photographer. I remember very well that when I got into photography I started with landscapes and nudes and sport photography till one day, I don’t know why, I discovered myself as a social photographer. Actually, the change is easy to understand: we had come from another continent, from the political movement we had lived in Brazil, we had studied politics, economics, and of course, it was only natural to turn to social photography. This is what we were doing at the time: Lélia and I were working really hard to welcome people arriving from Brazil, Argentina, Chile and Uruguay. Torture in Latin America was very tough at that time. There were people who arrived in France physically and psychologically destroyed and we worked in a big committee to get places for them in hospitals, to get medical care and apartments.

We had a small van, which we drove through Paris looking for people willing to donate chairs and old furniture so that we could try to furnish the apartments for our new friends. That was our life and when I decided to take pictures, this kind of photography became our life. It was only natural to go in that direction and that’s what we did, me as a photographer, and Lélia as an architect. Then we had our son, who suffers from the Down’s syndrome, so Lélia had to stop working as an architect for two years.

Lélia: Sebastião has mentioned the moment he left economics to become a photographer. We were very young and young people don’t think twice. When you’re young you just do what you like, what you want to do, and this is the big thing about being young: that you can change your life. We started from scratch. Of course, this life style was complicated, but it also had some positive sides. We worked hard and I knew that Sebastião had talent because we started to see the shows and the photography books. He actually had talent, and I said to myself, I must help him with his career. Sebastião has mentioned our second child, Rodrigo, who suffers from the Down’s syndrome. He was sick and of course it was very difficult for us to accept it and to understand how we could live with a child like him. But this experience strengthened us. I had to stop working for a while because he was sick, we had to go to the hospital several times and Sebastião was always travelling, but during that time, I’ve continued to work with Sebastião. I used to help him a lot, even printing photos and, as I had to stay at home for a year and a half, I organized his whole archive and all my pictures. It’s been nice, it’s been a nice experience because it made me fully understand what he was looking for and what was like to travel to high-risk countries during difficult times. I could see all the contact sheets of his reportages and it’s been extremely important because it helped me to understand what he was doing. I had to find a way for us to earn a living through this complicated profession. It was hard because we were constantly travelling, going to faraway countries to stay there for some time, and at the beginning it was extremely expensive: the films, the cameras, the trips... but we liked it because we had the opportunity to combine what we loved to do. I continued to work as an architect and afterwards I devoted myself exclusively to photography. But it has been a nice experience. An experience that continues after fifty-two year.

Sebastião: Fifty two years together, to today.

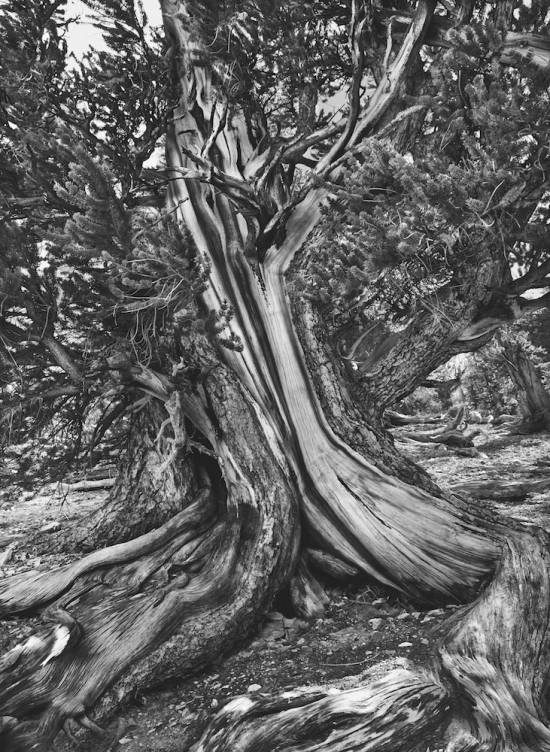

You see, this profession – and of course all the work required to make prints, as Lélia said – is very difficult, very expensive, and at some point I was forced to start collaborating with a few agencies around the world. I’ve worked for Sygma in Paris and it has been a positive experience, then I’ve worked for Gamma for four years, then I’ve worked for Magnum – which was the greatest agency of the world at the time – for fifteen years. In 1994 Lélia founded our own photo agency called Amazonas Images. But to keep it going, it was necessary to find another way to earn a living, and we had to work for agencies and cover the news. We worked for Stern magazine in Germany, for Der Spiegel, for Times and for Newsweek, and for many different magazines around the world. But I had a different approach from our friends and photographers who used to cover the news. Lélia and I wanted to give a specific direction to my career and life as a photographer: photography was not just a way to cover the news under assignment. I started working in Africa, I deeply loved Africa. According to Brazilians, Africa is the most important continent. If you take a metal coming from Brazil and a metal coming from Africa, you can melt the two together because one hundred and fifty million years ago they were located in one single continent. The minerals in Africa are the same of Brazil. The separation of the continents has split us up but we share the same inland. At the end of the XVI–beginning of the XVII century, many slaves were deported from Africa to Brazil, creating what we call the Brazilian race, an incredible mixture. Africa had an amazing influence on Brazil. So I started going to Africa, I loved going to Africa, I took every assignment there given by this agency, without hesitation. And we started to discuss about a body of work focused on Africa. I was an economist and at the time we saw incredible revolutions taking place all over the world, many of them in Europe. It was the end of the first big industrial revolution and the intelligent machines started to populate the production lines: the computers, the robots... and we expected to see the working class we had analysed and in whose name we had fought starting to reorganize itself. However, this old working class began to disappear, therefore we conceived a body of work on this theme. It took me six-seven years to complete it and we called it Workers. An archeology of the industrial era. I went all over the planet to photograph the world workers, the tragic heroes who worked to produce goods before the big change of our era. Then we put together a body of work that Lélia turned into a book called Workers and we organized a show, a big show that was hosted by eighty different museums all around the world. This body of work was amazing. When I was taking these photographs, I started to see that a new concept was coming out, the concept that much later we would have called globalization. We did not speak about globalization at the time, but we started to discuss about the possibility of reorganizing the human family as things were changing. In Brazil, when we were children, about 92 per cent of the population lived in the fields, whereas today about 92 per cent of the population lives in the towns. Normally, such a phenomenon takes place in more or less 560 years, but it took us only 40 years to reach this point. We live in a system of separate social conflicts: the same thing is happening in India, in China, in Mexico, in Indonesia... In fact, all these workers I was photographing were disappearing from these places but were also moving to another place. This big continent was a big producer of any kind of material: we had the steel industry, the car industry, the trucks industry, all the basic industries of the planet. And I was photographing various cities in which a new organization of the human family was taking place. Back then we started to conceive this body of work that we have just published now, Exodus. We saw that about two hundred million people per year were abandoning the fields all over the world and moving to the towns, giving life to a new urban society all over the planet. We conceived this body of work and for seven years I photographed these places and populations, as soon as I finished Workers. Then we followed this unique conflict in the former Yugoslavia, in Africa, Uganda, Burundi. All this violence that I had portrait while I was trying to capture the incredible movement of the populations, became such a huge part of my own life that at some point I needed to stop. I got sick, really sick. I had seen all that violence, I had seen so many deaths. One day I saw twenty thousand people die and it left me dazed. Twenty thousand in one day, but it wasn’t just that day: twenty thousand the day after and twenty thousand the day after the other... And all these refugees coming to Congo, Rwanda, Burundi... I got sick. I was about to finish this body of work when we came back to Brazil to stop photographing. Seeing what I had seen had been really hard on me. Moreover, my parents had become old, they had left us the farm, the farm where I grew up. We saw the farm and we decided, now let’s become farmers. But as soon as we started working in the farm, we realized that the land was dead, I mean, it was about to die. The eco-system of the land had been completely destroyed, including the lawns and the trees... Then Lélia had an idea and said, Sebastião, why don’t we replant the rainforest that was here a long-time ago? And I said, why not?, and our life embraced a new project, unrelated to photography, a project called Instituto Terra. Therefore, we started to replant the rainforest, we have planted about 2.3 million trees so far, we’ve rebuilt an eco-system that had been completely destroyed and we have transformed this land into what is today: one of the most fabulous forests on earth. More than 170 different species of birds live in this forest and we have planted more than 400 different species of trees, including all native species. As we were building this forest, rescuing this land, we came up with the idea of creating another body of work, namely the book Genesis. The concept of Genesis was amazing, it restored my desire to get behind the lens, so Lélia and I travelled around the world for about eight years to take photographs and the result that came out is the book that you have here. I needed to tell you this, to make you understand what photography means for us, what I did as a photographer, what Lélia did as a designer of books and shows. We didn’t come up with a concept, worked on this concept, then moved to another concept with the aim to create a nice book or a nice show... no... it was our life, our lifestyle, it’s with our ideology, our ethics, our philosophy of life that we have built our photography.

Lélia: It’s how we see our life, what we think about life, and how we imagine living in this world, with all the problems and all the happy things that come with it.

Sebastião: You see, while working on Genesis, we travelled a lot in Amazonia and I took a lot of pictures. We had planned one session about Amazonia in Genesis and, after we had finished Genesis, we stayed in Amazonia for three years and I would probably work there for another three or four years. In Amazonia, a tragedy is taking place. The planet needs a large amount of humidity, and I’m a hundred per cent sure that it all comes from Amazonia: the concentration of water, rainforest and humidity is extremely high there, due to the presence of a great number of rivers. All the rivers of our planet come from Amazonia, somehow. If we destroy the forest, if we lose this forest, it will be a tragedy. The Amazonia is the home of an amazing population: in Brazil there are about 250–300 different Indian groups, we have an incredible Indian culture in Amazonia and there is a huge number of tribes that have never been contacted yet. We have about one hundred groups that have never been in contact with the Western society. We were inspired to put together this body of work and the exhibition that Lélia has planned and designed. We are trying to see if it might be possible to create a political movement thanks to these Amazonian pictures. I came out of Amazonia in April 2016, where I was working with a tribe, then I had a meeting with five Brazilian senators. We know them well, they are our friends, and we discussed if it would be possible to make a proposal: changing the Brazilian economic policy regarding Amazonia because at the moment the policy is devastating for this land, it’s a predatory policy, and we would like to change it. Four weeks ago, we stayed in Berlin for one day and we had a meeting with the team of WWF Germany and explained them that, with a few friends we have here in Germany, we could try to bring the German government closer to these ideas. I became a member of the Academy of Beaux-Arts in France about two months ago and I am a member of the French Institute, L’Institut Français, which can exert pressure on the French Government. I’m certain that we can bring our friends together with us and see if these pictures of the indigenous culture in Amazonia, these physical pictures of Amazonia, with the forest, the boundaries, the animals, and the river, can create a body of work and give life to a movement with the aim of protecting this forest. You see, this is our life and we hope that in a sense it’ll become your life as well. Lélia for example has a plan for the shows in Brazil.

Lélia: For Exodus, we put together a show about Amazonia: we printed high-quality posters of a selection of picture. We wanted to create a nice exhibition and it has been quite easy, we just had to frame the posters and hang them on the wall. What I loved about this concept is that it opened up a series of possibilities, and that everybody could see our pictures, they were easy to access. Therefore, we embraced this idea, the first show was for the landless movement in Brazil. We realized a book called Terra and then we put upthe show. I planned the exhibition and we printed, I don’t know, something like 2,500 posters for various shows that took place at the same time. The landless movement distributed the posters all around Brazil and here, in Europe, we worked with an institution that brought this show everywhere. It’s been a great experience because many people could see the photos at the same time and discuss about it. A lesson to be learned. Carrying these posters and hanging them on the wall is very easy. It really is easy, and we are thinking about something similar on Amazonia… I don’t know, during the next three-four years or more Sebastião will take pictures and then we will begin to plan the show.

Sebastião: You see, I said that photography is not about the images that we like, it’s our way of life. I have created several bodies of work. For example, when I was working with the oil industry in Venezuela for the book Workers, Saddam Hussein, who had invaded Kuwait, set alight the oil wells in the country. You probably remember this, it was 1991 and this represented the biggest ecological disaster of the planet. Six hundred oil wells burnt at the same time and, just to give you an idea, in about ten months they burnt or dissipated more than one million barrels of oil. It was incredible and of course I went there to shoot these pictures. But I edited them just a little bit with Lélia, with whom I was working on a much more important body of work, Workers. They were included in the volume but we never edited them with care. During the last year I’ve kept saying, Lélia I know that I have a story here, and I went deeper into editing these pictures. It is a big book called Kuwait: a desert on fire. You see, I had a big chance, the great opportunity to live my life within this specific historical moment that we are living in; through my photographs, I had the opportunity to ride the waves of history in the exact moment we were living it.

We don’t approach photography as press agents do, we don’t go to a place to take picture simply because something big is happening over there. When you travel to shoot photos, you bring a big and long heritage with you. In the fraction of a second, in which I am there to take my photograph, I carry with me my father, my mother, the light I saw when I was a child in Brazil, in this farm, that was mainly surrounded by a rainforest. The rain season was amazing there: I reached the highest point of our land with my father to see from up there the arrival of the rain season and its incredible light. And when I take a picture, in this fraction of a second, it’s all there, all these topics that we have studied together, sociology, anthropology, geopolitics, economics... it’s all with me. I stand by my ground, my ethical point, my philosophical point, my social point: it’s all there, I have made the choice to live like this for my whole life with my wife. We have lived together for fifty-two years, we’ve lived our life together and all these things come together in the end and when you take a picture in this fraction of a second, it’s all there. Photography is not objective, it is subjective. If you ask a hundred photographers to describe the same event, a hundred different pictures will come out because each one of them comes with a different heritage. In this specific moment, you have your background and you must tell this story through your pictures and I think that this is one of the most amazing aspects of photography. Photography is a recent technology, it’s about 120–150 years old. And it’s coming to an end. Photography is about to disappear, now there are images everywhere. You have all these telephones, you have all these digital cams. And now photography has become a concept. You don’t touch the photos any more. Think of all the photographers who do prints, touch prints... photography is about your father and your mother taking pictures of you when you were a child and bringing the films to the shop at the corner of the street where a photographer made these small prints that were then glued to the album pages. They became your history, your memory, all the photographs brought a huge history with them. Now photography is about to disappear because, if you lose your telephone, if you lose your computer, then you lose your photographs. But it’s not really a big deal. What is important is that photography has become a language: you send pictures by mail and that's it. You communicate via photography. Maybe today photography is all about that, and as photographers we should grab this opportunity. But what we have lived is incredible. I had the opportunity – as I just said a few minutes ago – to live my life and my historical moment and these pictures are able to tell a story through what they preserve. Photography is so powerful, photography is so incredible that, I tell you, in 20 years–40 years from now, the pictures we have taken as documents, just to give you an idea, as our way of life, will be of huge value because they talk about what is vanishing, they portrait the world we are living in.

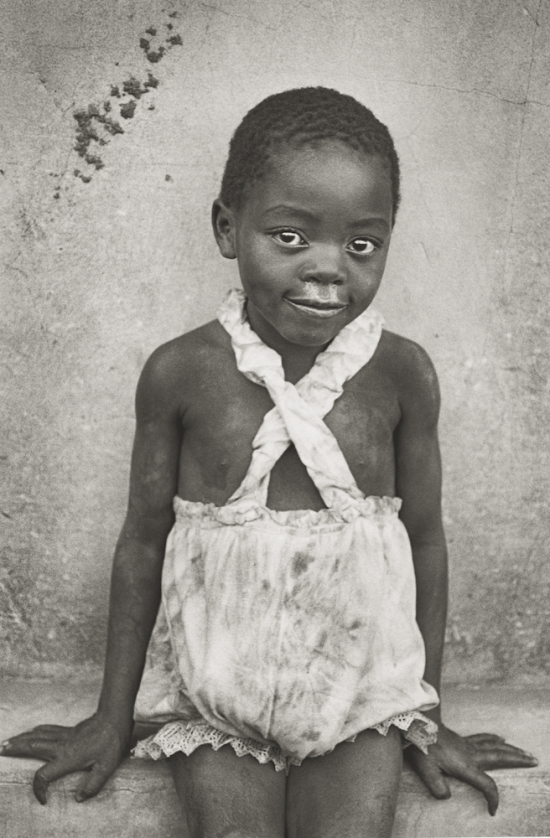

When I was taking pictures for the other book, Workers, every time I went to a refugee camp, I was surrounded by children and I couldn’t work because they were jumping around, they wanted to be photographed. Even if they are starving, even if they are suffering, they are still kids. And when there is somebody new out there, somebody who changes their routine, they get excited. Sometimes taking pictures was really hard. One day in Mozambique I had fifty kids around me and I said: lads, if I take a portrait of each one of you, will you allow me to work then? And they said, Yes. There were fifty kids sitting here, I have… I don’t know, a slice of wood there, a tree down there... one of them seats there and I take a picture. They came to me one after another, I put a 60 mm Leica lens on my camera. I used to work with a Leica camera at the time and that was perfect for portraits. I’ve taken a portrait of each one of them, it was necessary to really shoot the pictures, because kids know when you are just pretending to shoot. So I took these pictures and then they were gone. They were very happy, we had made an agreement, they respected it and I was able to work. Two hours later another group arrived, so I took pictures again and it went on like this. On the next trip the same thing happened: I had the solution up my sleeve, so I made my proposal, the guys accepted it and I took the pictures. When I arrived in Paris I edited these pictures and put them aside to focus on the Workers book and did not print them. Then one day I looked at them and in that precise moment I realized that these kids who had come in front of me were not bothered by the group surrounding them. In that moment, the relationship between the photographer and the person that was being portrayed was authentic. Through their eyes I could look into their soul and see their life. Then Lélia took the decision and said, Sebastião, we must give a place to these kids. She had the idea of devoting this book to the kids. Therefore, she created the book with these portraits that was entitled Portraits of children from the Exodus. That was the first title of the book.

Lélia: We did one show, an Exodus show, in Rome and, of course, each location is different and we must adapt to it. The show consisted of 350 pictures and 90 portraits of kids. I didn’t want a big room and I printed all the portraits like this one, then hang them with little space between them. But it was so powerful, when we entered the room and we saw all those pairs of eyes looking at us. It really had a strong impact and, you know, these kids actually helped us to develop this subject because they were there and they didn’t know what exactly was going on, but enjoyed life as kids, as if they were at school, and that’s the important thing.

Sebastião: From that point on, sometimes I’ve been called the photographer of the world misery, but that’s not true. Every person I have photographed for this book was not living in misery, these people led a normal life, they had reached a balance in life, they had a house, they gave food to their kids, the husbands loved their wives, they loved their kids and each other, till one day, they didn’t know why, they were forced out of their houses, out of their lands, they found themselves on the road with nothing. But these people were not desperate, they were leading a hard life, they were suffering from various diseases but they were going through a transition. They arrived from a stable point and were heading towards another stable point, the one they were looking for. They moved as a community and what impressed me the most in these groups were the elderly, the very old people who had worked all life and were ultimately ready to end their life in peace. Now they were on the road and for them it was another story. It was very different for the kids as well, because they had no idea what they had lost when they were forced to leave. Exodus and Children probably represent the strongest experience of my entire life.

You see, the only difference between today and 16 years ago is that what was happening in Asia, Latin America and Africa has now reached Europe, it’s at our doors. The situation is exactly the same, there’s nothing new, the only new thing about it is that we are experiencing this in Europe, but this situation is exactly the same of many years ago.

Bibliography

Kuwait. A Desert on Fire, Taschen 2016

Exodus, Taschen 2016

Children, Taschen 2016

Other Americas, Aperture 2015

The Scent of a Dream, Abramsbooks 2015

From my land to the planet, with Isabelle Francq, Contrasto 2014

Genesis, Taschen 2013

Africa, Taschen 2007

Sebastião Salgado, Contrasto 2004

The end of polio, Bulfinch Press 2003

An uncertain grace, Aperture 2005 (with Eduardo Galeano and Fred Ritchin)

The Children: Refugees and Migrants, Aperture 2000

100 photos de Sebastião Salgado pour la liberté de la presse, Reporters without borders 1998

Terra: Struggle of the Landless (with José Saramago), Phaidon Press 1998

Workers, Aperture 2005

Sahel: The End of the Road, University of California Press 2004

Filmography

The salt of the Earth, directed by Wim Wenders and Juliano Ribeiro Salgado, Decia Films 2014