There are books I pick up only because I am fascinated by the cover, or because I like the title. Then I open them and find out they are just as beautiful inside. I discover a wonderful world made of stories of passion and enthusiasm. I realize I ignore much more than I suspected. Every time, I rediscover why I unconditionally love these objects made of printed paper. This is why – considering that I work with books – I have chosen a common denominator for these books: #MIRABILIA.

1a, b Horseshoe crab; 2 Penaeid shrimp; 3 Lobster; 4 Spider crab; 5 Crab; 6 Eggs of a crab; 1-4 Porcelain crabs

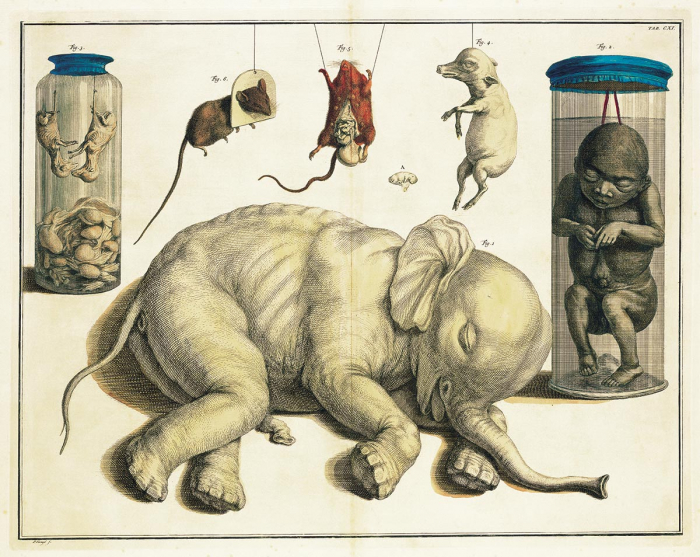

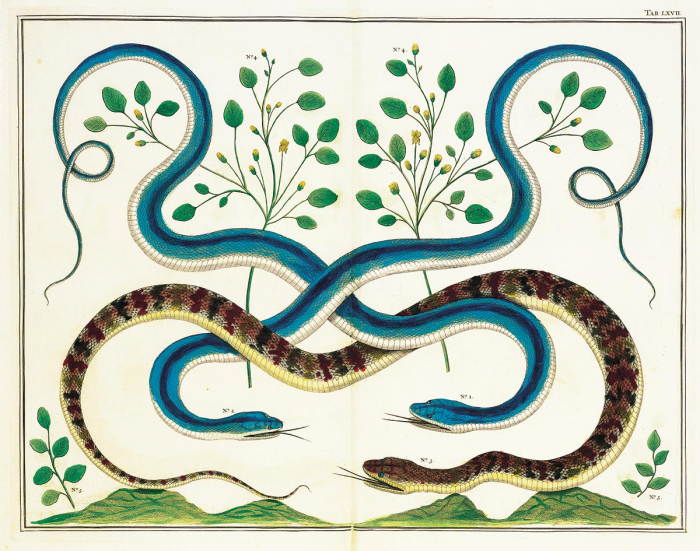

Cabinet of Natural Curiosities is a nice title. The red of the coral looks beautiful. And inside there are fascinating plates representing animals, shells… but here comes the surprise: I read the book and, as I look for information about Albertus Seba (1665–1736) – I am a very ignorant person but fortunately not so full of complexes to refuse to learn new things – I discover he was a Dutch pharmacist and collector, who didn’t make the book’s inner plates himself but commissioned them instead.

There was a time in which being a pharmacist implied many years of apprenticeship at other pharmacists’, in order to learn their recipes and the tricks of the trade. A time in which drugs were produced using natural ingredients; in which creating remedies was considered as an art, which was made possible by using components of animal, plant and mineral origin; in which new recipes were tested by using and collecting natural specimens, sometimes even found in faraway lands. At the time traveling, knowing, getting information was the result of an effort, it meant undertaking an adventure and entirely devoting one’s life to it. In this world of commitment and sacrifice, with temporal dynamics that were completely different from those we experience today, with a vision of the world and his riches confined to what you could see with your eyes or hear from those who had seen it, or – if you were lucky enough – you could read, it happened, as in the case of Albertus Seba, that the passion for collecting ingredients went beyond the immediate pharmaceutical applications. It happened that the pharmacist created such an important collection of natural history that it crossed the borders of Holland reaching us nearly three centuries later. It happened that this pharmacist decided to entrust some artists to reproduce the pieces of his collection in order to create a work in four volumes entitled Locupletissimi rerum naturalium thesauri accurata descriptio, whose printing he partially financed himself. Albertus Seba was neither a pharmacist with the hobby of collecting, nor a collector who was also a pharmacist by hobby: he was a successful pharmacist who – for and thanks to his job – had the possibility to obtain the pieces of his enormous collection. This is what I call enjoying your work. It is said that every time a ship entered the port, Seba hurried up in order to reach it and administer his remedies to the exhausted sailors, so that he could buy cheaply – or get in exchange for treatments – any natural specimen seafarers had brought home. Over time his collection became so vast that it gained a great scientific prominence in the field of reptiles, insects and sea creatures, and it greatly helped to identify the different species, remaining – luckily for me and maybe for you as well – connected with the older Cabinets of Curiosities for the attention paid to bizarre, rare, and astonishing things.

There was a time in which starting and owning a Wonder-room or Cabinet of Curiosities was about much more than displaying a collection of objects. A wunderkammer was above all a place for studying, for creating intellectual incentives and satisfying one’s investigative instinct, or showing off one’s education and wealth. The wunderkammers were arranged in order to facilitate people’s understanding and to make clear the connection between the elements of which they were composed. The display of the various objects in the room – some of which were placed on tables – allowed the observer to make a visual correlation between the single elements and to identify the connections between them. The organization of the Cabinets of Curiosities, that to our eyes seems chaotic and heterogeneous because we are accustomed to simplified and aseptic museum display cases, was based on this web of meanings and, in addition to classifying objects according to their specific material properties, it included references to religion and alchemy. But above all wunderkammers – contrary to what happens today in the trendy shops in Milan and New York that propose them again – used to contain books as pieces of the collection itself. Books acted as a commentary to the collection, they offered a key to understanding the subject and allowed to identify and systematize its elements. The books, with their illustrations, completed these collections by filling gaps (if any) and compensating for deficiencies. Some of these collections later became books, like Seba’s Thesaurus – an incredible source of information, used by Linnaeus himself to improve and expand later editions of his Systema Naturae.

There was a time in which everything implied a new discovery: observing, collecting, gathering objects was considered as a useful pastime but above all an important part of one’s education. This is how people participated in scientific enquiries, directly obtaining the knowledge available at that time and maybe even contributing to it. Many objects were hard to get or preserve, and the collections of drawings could replace or complete the missing or flawed pieces. This led to the creation of true “museums on paper”.

There was a time in which travelling was a prerogative for few people and also entailed considerable risks, a time in which people didn’t know our planet’s real extension, and in which some naturalists started to travel in person, in order to document what they saw through illustrations that they made themselves, or that were made by artists that accompanied them for this purpose. On their return, sketches and descriptions made on the spot became travel books, true natural histories of the regions they had visited. Outstanding was the work of Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717), a German artist who travelled throughout Surinam at her own expenses and on her own initiative from 1699 to 1701. In 1705 she published Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, consisting of sixty large illustrated plates and detailed descriptions (INSECTS OF SURINAM, Taschen). Merian’s artistic still life illustrations aesthetically influenced the design of the first volume of Seba’s Thesaurus.

The Thesaurus represents an important collection of natural specimens dating from the beginning of the Eighteenth century. The existence of this book has allowed the collection – static in itself – to become movable and always accessible for the many people that were interested in it – although the collection itself had been scattered here and there for a long time.

To me the existence of the Cabinet of Natural Curiosities means that – with all the knowledge and the technology available today – we can still think we can know or study through direct experience, we can devote part of our time to observing the world in the smallest details with different – but above all curious – eyes, and discover how much #mirabilia has always been around us.

What would happen if we told our children about Albertus Seba and the meaning of wunderkammer? If we presented them with a Little Box of Curiosities and invited them to fill it with all those #mirabilia they can find even in the streets? And what would happen if together with our children we looked for information about Seba’s findings using google or our home encyclopaedia (if we have one).

I see a new life style. Endless studies that would make both our children and us much more aware of ourselves and of the world that welcomes us.

Original Thesaurus on-line: https://archive.org/stream/Locupletissimir1Seba#page/n0/mode/2up

CABINET OF NATURAL CURIOSITIES

by Albertus Seba

TASCHEN

hardcover, 592 pages, 140 x 195 mm

Italian / Spanish / Portuguese edition

ISBN: 9783836558099