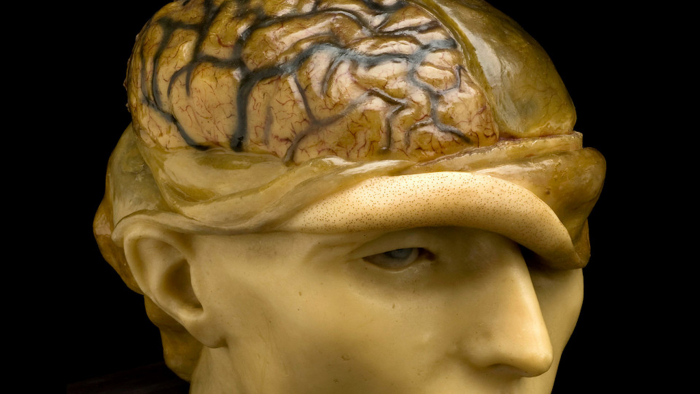

At the beginning of the Thirties, at the Montreal Neurological Institute, the Canadian neurologist Wilder Penfield was in search for a surgical treatment of epilepsy. The surgeries he was determined to carry out consisted of recognizing and subsequently removing the areas of the brain that had caused the disease or had been completely damaged by it. But how shall one know for sure how and where to cut with accuracy?

In order to better understand which areas were sound and which ones were damaged, Penfield decided to operate under local anaesthesia. Patients remained conscious throughout the surgical procedure and could talk and answer the doctor’s questions, although their skull-caps had been removed and their brains were exposed. Everybody knows that this organ is immune to pain because it lacks nerve endings; doctor Penfield could therefore carry out his experiments without causing pointless sufferings.

The neurologist used to touch the brain with an electrode and apply a little shock, in order to find his way through the sound and dysfunctional areas, sticking small numbered pieces of paper on the tested areas. But, during one of these pre-operational experiments, something extraordinary happened.

While he was operating a thirty-seven-year-old housewife, Penfield stimulated an area of her temporal lobe with the electrode and all of a sudden the woman said that she thought she “had seen herself give birth to her daughter”. Since then, for twenty years Penfield had been touching hundreds of brains with his electrode: only a small percentage of his patients experienced a surfacing of more or less hidden memories, but they were numerous enough to convince the doctor that memory is a “permanent recording of our stream of consciousness; a much more complete and detailed recording than the set of memories one can recall of his own will”. Apparently this kind of electric recall could bring to light memories of which the individual wasn’t consciously aware.

Penfield’s patients recalled a great number of extremely detailed memories: some remembered a boy creeping through a hole in the fencing during a baseball match, some relived the moment when they pulled a stick out of a dog’s mouth, and some saw the circus caravan at night, that same caravan they had seen when they were children.

Penfield’s discovery seemed absolutely important. Is it true that our memory is a huge hard-disk where everything is recorded and stored, and we only need to know the correct “directory” in order to recover the right file?

Unfortunately it is not as simple as that. When Penfield revealed the results of his researches during the Fifties, the press explained it all by means of the simplistic metaphor of the tape-recorder, thus spreading the idea that the brain stores any experience with perfect accuracy in the smallest details even if we are not aware of it. Journalists omitted the fact that less than 5 per cent of the patients that Penfield stimulated with the electrode relived some memories; furthermore, no other contemporary surgeon has ever got such impressive results, even if some researchers noticed that brief hallucinations can be provoked by an electrical stimulation of the brain. Therefore, after all, maybe Penfield’s patients did not really remember, they imagined things.

Today only a few scientists believe that our brain is a library of unaltered memories, even because several psychological researches suggest that memory is not firm but is continuously reinvented and elaborated. Here follows a concrete example: when people were shown a series of pictures dating back to their childhood, including an edited picture of them as children at a fun-fair (where, actually, they had never been), most of them “invented” a memory of that fictitious moment, and reported the details of that “unforgettable” day.

Apparently, like skilful directors, we usually alter our memories as time goes by in order to adapt them to our emotions, to make them more acceptable or simply to make them sound more interesting to our friends… and we end up believing in them. All this casts a strange light on the eye-witnesses that, after several years, perfectly remember that the killer was wearing a blood-stained grey coat but it also casts a strange light on our own past, on the way we think we remember it, and all in all on our beliefs about who we are.