Graciela Beatriz Cabal

by Lina Vergara Huilcamán

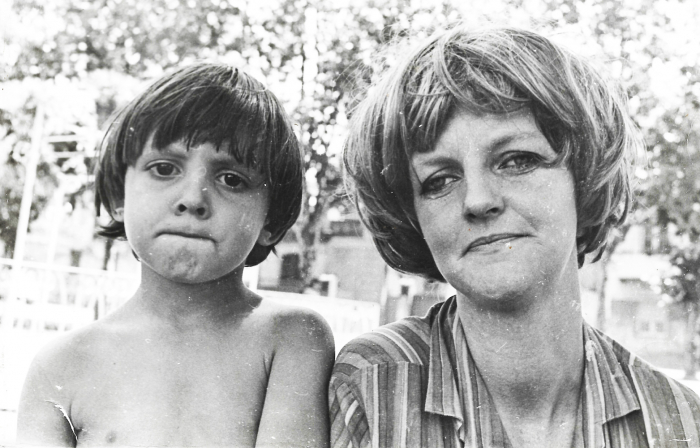

it was a little less than twenty years ago. my little Ciopi still a little girl. and I an housewife. a far away, endless, time when I enjoyed the luxury of going from library to library in Santiago in search of books to read together. funny books. books that could make her laugh. that’s how we came across Jacinto and Batata. and Graciela. Graciela Beatriz Cabal. their author. and after so many years. after moving house and changing continent many times. here we are again. Graciela and I. after twenty years. in the meantime unfortunately she passed away. but not her books. which are going to be published in Italy now. those same Batata and Jacinto. which we’ve read and reread dozens of times with my Ciopi when she was still a little girl.

in the meantime I’ve grown up. I’m not in my twenties. nor a young wife in love. nor a new mom. nor a housewife any more. but I’m still fond of reading. and I developed a curiosity for other people’s life, which I listen to and write down. in these short interviews. and so. by publishing her works. I was lucky enough to get in touch with her son. Pablo Pla. who gave me the chance to know and tell you a little bit of this great woman. author. reading ambassador. argentinian. with the feeling that this will mean more to me than I imagine now.

“Tomorrow is march 8th. I can’t not remember how important women’s rights were to my mother, Graciela Beatriz Cabal, who wrote about them in her own way, way before they became a hot topic as they are today.

Society’s problems, women and their rights, children’s rights, democracy… were her life. I remember her working devotedly. Going from library to library in the remotest villages in Argentina and abroad, carrying books, chatting for hours with people she had just met. At night I always saw her writing. Tales that might never be published, many of which were based on true stories that she told from an ironical point of view, maybe exaggerating something here and there, but still true.

As is the case with La Señora Planchita (Little Mrs Ironing), who was our upstairs neighbour, in Avenida Córdoba 4100, Villa Crespo, in the heart of Buenos Aires where we lived, in a very small 3 room apartment, whose walls were so thin you could hear everything and everybody. Mrs Mirta – this was her real name – was one of those women who only stay at home and wash and iron and cook for their husbands and their kids, who then shone thanks to her efforts. Quite different from my mother who was always travelling, coming and going and with a thousand things to do. My mother opened the window and called her, and Mrs Mirta looked out of her window to have a chat. Or they asked each other for some sugar or yerba for the mate, two things you always need here... And every time my mum went upstairs she always found her in tears in front of the television, because of some soap opera she was watching. And she cried and she ironed the whole time… just like La Señora Planchita.

Starting from everyday – domestic – reality and never scolding, my mother’s aim was to rouse these women, to make them think and consider different ways of life.

She wasn’t much of a cook, she wasn’t able to be a traditional mother, maybe because she didn’t have the time, busy as she was with work. She didn’t bring us – my sisters and I – to the park, it was my grandma who did this kind of things, she has always helped her a lot.

She always told me that one day she found us in the living room, there was yerba mate scattered all over the floor, we were little children, so she scolded us and asked us why we had done that. We answered that we were pretending to be at the park… so she took us and brought us to play at a real park.

She worked a lot, but also cared a lot about our achievements at school, and from a very young age she gave us books to read. And the fact that we were children didn’t mean we had to only read books suitable for our age. There were always a lot of books at home. Reading to me has always been, and still is today, the only way to learn how to write and talk properly.

We always went on holiday in unconventional places: to the Valdes Peninsula, to climb a mountain… until with age she felt the need to stay quieter.

She always said that when she entered a house the first thing she looked at was the book shelf, the library. She didn’t like houses with perfect, untouched, books. In her opinion books had to be used and broken and scribbled all over, stained with dulce de leche. They had to be touched and lived and if by chance they broke, oh well, you could buy some other… but books were not something you just put on display.

She loved to teach and chat, especially with women, to promote reading and stimulate their imagination. They invited her to far away places, like they used to do back in time (and still do today), to present her books and sign copies, but then she decided this was not enough, and she started to read them aloud. I was still a child, so it was some decades ago, she travelled, presented, read aloud and signed the books. She always brought a lot of books with her, some she gave as a gift to people or libraries, therefore a lot of libraries are named after her. She went and read her stories aloud in Ushuaia, Jujuy, in every possible place in Argentina. And also in the cities, for example in La Matanza, a very poor area in Buenos Aires. So they invited her to literature conferences, where she always went, keeping on reading in her spontaneous way. She read aloud in Argentina, in Mexico, in Central America, in Ireland, and in some other places in Europe. Wherever she had the chance to go.

She created a style of writing for children and youngsters, whose intelligence she always respected. She addressed them with no moralism and with the express purpose to make them think. She also wrote two novels for adults, and died after finishing the second.

Her books are still used in Argentinian schools, but her most important heritage was the promotion of reading in our country, the creation of libraries in isolated locations.

She got the passion for reading from both parents, but inherited the one for writing from her mother, my grandmother Beatriz, who gave up the dream to become a writer because of her role of traditional housewife.”

Pablo Pla

thanks to Graciela’s writing. to the way she told stories with sweetness. and simplicity. and with a great femininity, free from any gender complex. I can find myself in her texts. in my everyday life story. as a little girl. a mom. a woman.