“It’s all a waste of time,” he yelled one day. “Everything begins only to end. The moment you were born you began to die. That’s how it is with everything.” (Janne Teller, Nothing, 2000)

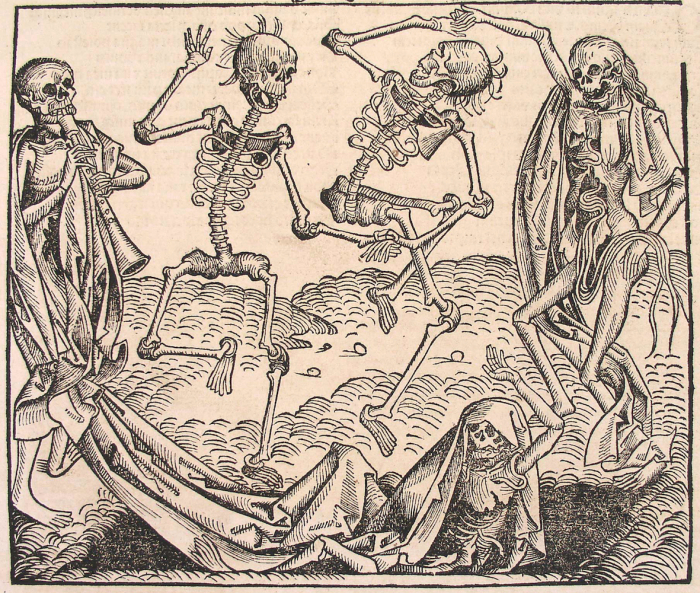

In Janne Teller’s biting story, the young Pierre Anthon understands the limitedness of life and settles on a plum tree branch, becoming a troublesome and undesired voice of conscience that constantly reminds his school mates how meaningless life is. The boy triggers the kids’ search for the ultimate meaning of things, a quest that quickly degenerates into a sort of vicious and atavistic game, a Lord of the Flies with an existentialist flavour. But well before the arrival of the existentialists, western culture had to put up with another Pierre Anthon. The cruel pebble in the shoe, the little voice that like a persistent woodworm took pleasure in destroying every reassuring construction of sense, was a holy book: the Koheleth. Also called Ecclesiastes and dating back to the IV or III century b.C., this book is still somehow the most “shocking” one of the whole Biblical anthology. It’s shocking because that reiterated phrase – havel havalim, “vanity of vanity” – is a stone that still weighs on our shoulders. Every horizon disappears when faced with the “breath of breaths”. Every human action is turned into something futile and illusory by all-levelling Death: piling up treasures is useless, just like the quest for wisdom is a sign of stupidity in the end. It’s impossible to raise barricades against a fate that wipes away every human effort with a light breeze. Faith into the goodness of life and the splendour of creation, even the idea of a saviour God, that of the Exodus or of the Sinai desert, cannot find a place in these cruel pages: nothing new could ever bloom “under the sun”, on the Earth as we know it. “It’s all a waste of time”, yells Pierre Anthon. “All is a breath!” says Koheleth. An obsession, an unavoidable question. And since it seems there is no trace of the strongly yearned “meaning” in this world, Medieval theologists find it in what awaits us after death. Christians learn the contemptus mundi, the disdain for worldly pleasures and the physical body – governed by impure and deceptive senses – and focus all their expectations on the upcoming Kingdom and the glorious body; they try not to give in to the illusory nature, which consists just in “following the wind”, and get ready for “true” life. But this eschatological hope is not enough: death still scares us. Therefore, on the fringe of official theology, people try to react in a different way. There’s an incredible strategy, elaborated outside intellectual environments, which is more poetic and more instinctive: faced with the unbearable certainty of the end, people start to dance. Folk dances are documented to have taken place inside churches and graveyards during the Middle Ages, “liturgic” balls improvised even in the presence of priests or bishops (a synonym for bishop is presule, prelate, he who opens the dance); but at the same time a great number of stories about dead bodies that used to rise from their burial recesses at midnight and danced to draw the livings among their ranks were hugely popular. During the Middle Ages another peculiar dance appeared, the chorea machabaeorum, which largely influenced western culture. As its name suggests, chorea machabaeroum was inspired by the Books of the Maccabees or, more precisely, by the cult developed during the Middle Ages around these seven brothers that rebelled against the Seleucid dynasty, becoming martyrs. In the Fourth Book of the Maccabees, considered as an apocryphal book of the Old Testament and widely known in the Christian tradition, is written that the seven brothers “defeated their fear of death dancing in a circle of seven”. This passage, perhaps, gave birth to the Medieval dance, in which members of the clergy and laymen alike met up in a joyful ball before retreating, to represent the Maccabees martyrdom. According to some scholars, the Maccabees dance, indeed, was a precursor of the Dance of Death, one of the most successful iconographic subjects of the whole European art tradition, in which a series of skeletons dances unrestrainedly to accompany moribund people to the grave. A dance with a double meaning: on the one hand it represents the final dance “from whose embrace no living man can escape”, as written in the Canticle of the Sun by Saint Francis of Assisi, and that levels the conditions of both peasant and emperor, prince and damsel, bishop and artisan. On the other hand, it’s an exorcising, carnivalesque dance that helps defeating the fear of death. Therefore, here it is what might be the sole answer to Koheleth’s (and Pierre Anthon’s) question: to dance. Living life like a round of dance, light on our feet, in spite of the absence of meaning.

In spite of death itself:

You’re the guest of honour of the dance we play for you

Put down the sickle and dance round and round

A round of dance and then another

And you’re no longer the master of time.

(A. Branduardi, Dance in minor sharp F)