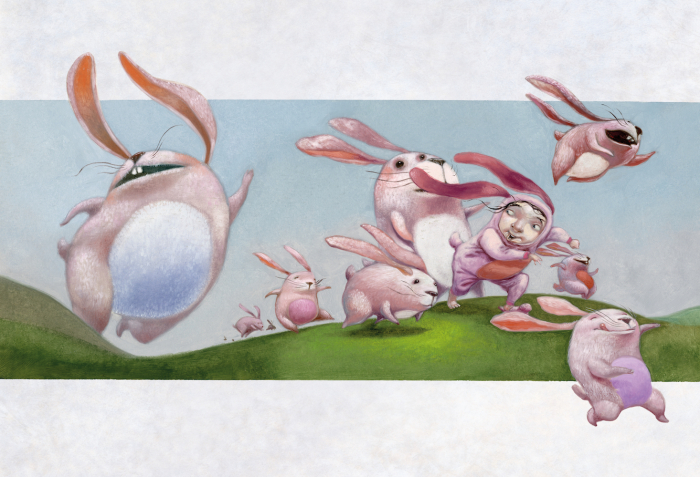

A little girl falls in another dimension, like Alice in Wonderland. But this time there’s no underground world to welcome her, quite the opposite: sinking in the pages of the book that she’s holding in her hands, she plummets through the blue sky and snow white clouds. In her fall she loses one slipper and then risks crashing to the ground, but a huge canary quickly dives providing a soft landing and saving her life. This is the beginning of a beautiful journey: carried by her new friend, the girl arrives in a grassland where a family of pink rabbits offers her a pink rabbit costume that she puts on. They take her on an adventure through lush hills and dark caves, and introduce her to a piglet and a cheerful gang.

No one is missing: giraffes, cows, monkeys, elephants, horses and birds… all ready to turn into lovely playmates. There’s even a colourful sea turtle that welcomes the girl and her inseparable friend piglet on its shell for a crossing. From this point of view, Amigos could be the typical picture book about animals that you usually buy for kids, just like the one that the girl in the story gets as a gift from her mum. But this is only one side of the story: the child travels with the imagination to another world, meanwhile the real world carries on. A double track that is projected into a chromatic level thanks to the alternation of coloured tables filled with the joy of life and black and white illustrations that slowly take on a disturbing connotation. The vast open spaces, the sky, the grasslands and the sea are counterbalanced by urban landscapes with their boundaries defined by the architecture. The soft rounded world full of colours is opposed to straight lines and the sharp corners of the city and the house, with its doors, staircases, rooms and drawers.

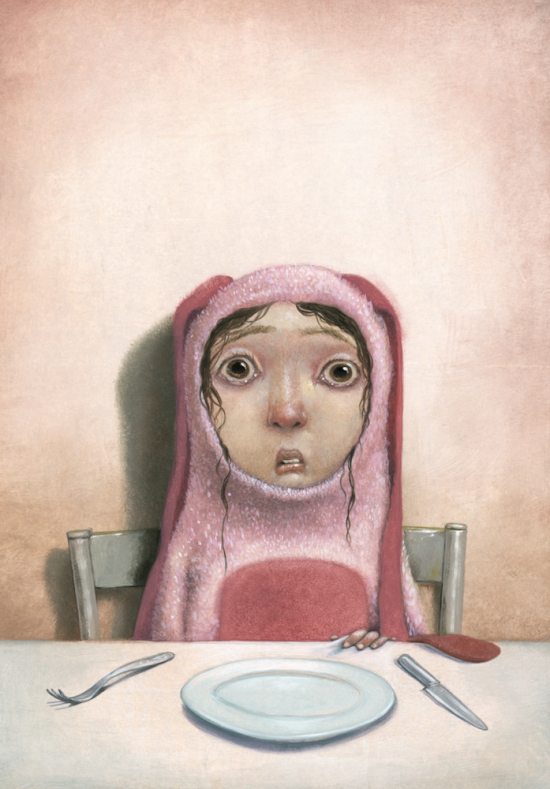

The girl and the animals play in complete harmony with nature, but we cannot abandon ourselves to that world because the book forcefully brings us back to reality. The carefree running in the grasslands is interrupted by the sudden appearance of a drawer full of kitchen tools that, aided by the greyscale of the pictures and the strong contrast with the previous colourful ones, look extremely threatening in this context. The tension grows until we finally understand what’s their purpose when a blade chops down an onion. These tools and gestures are part of our everyday life, however Roger Olmos is able to represent them in an effective way which conveys the anguish of an imminent tragedy. Now the hands put down the knife and take a baking pan from the cupboard, then cut out the games with the liana to extract a dish wrapped in foil from the fridge. Finally, the girl is torn away from her daydreaming, just like us. It’s dinner time and the child is sitting at the table in front of her empty dish, then the lid is taken off the server tray, revealing the friend that was playing with her just a few minutes ago. She recognises him straight away, even if he doesn’t have that pink colour anymore and is crunching down, distraught, the smile contracted in a grimace of pain. The two worlds finally merge in the image of a shocked child dressed in a rabbit costume. And the piglet of the fairy tale appears on the tray, still alive, with sweet and imploring eyes, while the knife begins to hurt him. In spite of everything, the book has a happy ending, the two friends embracing and staring at the horizon. A promise of peace between all living creatures, a horizon that we can reach through a slow journey. The realisation that we have a choice and that the only logic and ethic choice for the planet well-being is changing in order to reduce the suffering that we cause on a daily basis to many living creatures that have feelings just like we have.

Roger Olmos does not need words in order to clearly and vividly express this message, which he holds close to his heart. Avoiding the aggressive and judging tones that usually lead to violent reactions and defensive arguments, the artist masterfully uses his visual code to let the contradiction of our life flow to the surface.

From the book title emerges a keyword which remains unsaid, but pervades all the images of the colourful world: empathy. The little girl wears a rabbit costume while she is playing with the pink rabbits, a costume that she will carry with her in the real world in order to put it on again at the moment of her epiphany. A costume that the author decides to wear for the picture at the end of the book, in which he holds in his lap his dog. An invitation to literally live in the animals’ skin, to understand that they are able to suffer, exult, love like we do and to imagine how it would be like to be deprived of our freedom and undergo the physical and psychological sufferings we carelessly inflict them. And, last but not least, to realise that we can put an end to all this.

There is no difference between pets, like the dog in the author’s arms, and the animals we consider mere food. When seeing a dog or a cat, or a cow or a chicken, children are moved by an innate wave of affection, they want to pet it or play with it. They consider them all as friends. Similarly, the adults tend to ignore the fact that the steak or the sausage in their dishes are pieces of those animals that they would never hurt with their own hands. As a matter of fact, in the black and white illustrations, the mother’s sweet features depicted in the first pages, when she buys the book for her daughter and hugs her at home, lately disappear, leaving place to disconnected hands that cut and cook, or serve the table. In this way, the images suggest a disconnection between the actual persona and the mechanical gestures, performed without thinking. This disconnection is the only reason explaining how the mother was able to give to her daughter a book that teaches her to love the animals and then offer her their sufferings on a silver dish, just a few moments later. The contradiction is crystal clear to the little girl of Amigos and we are all invited to overcome it.

This book can mark the beginning of a journey or guide us along the way because, as Olmos states in the epigraph, the words expressed in favour of this topic can be rejected or forgotten. A book, no. A book is forever.