Urban chronicles, blood and guts, Latin America. Three instant mental associations, concerning not only Pedro Lemebel, but also Enrique Metinides, who was given a camera from his father when he was a child and since then has never stopped shooting.

Since the beginning, his photographs have captured what James Graham Ballard would describe dozens of years later in Crash and David Cronenberg would adapt to a movie: violent deaths, car carcasses, blood. Because Metinides immediately specialized in photographs of car crashes – seeing the first victims of a murder and the first corpses already as a child.

Metinides started working as a photographer in the second half of the 1940s. His first photograph was published when he was only 12 years old and at the age of 13 he joined the staff of La Prensa, the Mexico City newspaper, as an assistant photographer. During the following 50 years Metinides came across death in its most tragic forms: overturned buses, fires, train derailments, plane crashes, murders. “If all the victims and the corpses I have seen caused by these accidents could be piled up, the heap would be as high as a mountain. I got to witness the hate and evil in men. The instinct of killing for the sake of killing. I saw incredible crimes committed by children and adults. Sometimes they would rob them of almost nothing. And I have treated every death as a film frame”.

In a video interview where he sits in a small drawing room lined with crucifixes, full of folders of archived materials and curious scale models – police cars, ambulances, fire trucks – Metinides tells the story of some of his best known pictures. One of them shows the back of a woman walking down a busy road holding a little white coffin. Her daughter’s body will be put in the coffin and the woman will walk miles, carrying the burden of her sorrow, because she doesn’t have enough money to pay a car for the transport of the coffin.

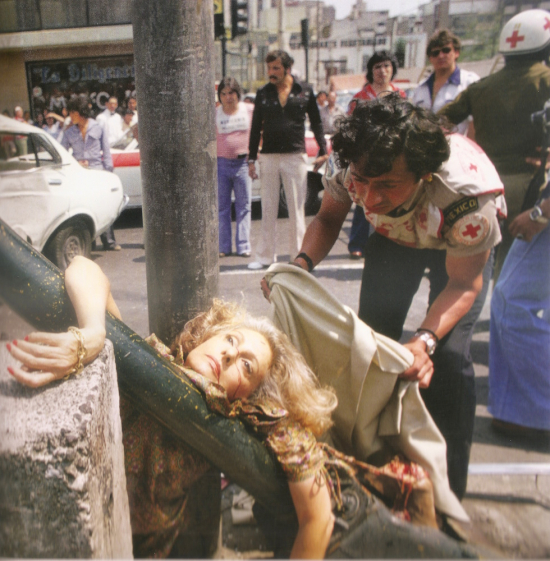

Another picture shows the beautiful face of Adela Legarreta Rivas, a journalist that died in a car crash in Avenida Chapultepec while she was walking to a press conference to launch her last book: liquid eyes, a few trails of blood and organic matter, blonde ringlets and a graceful hand with polished nails. Almost a tabloid’s picture, incredibly sensual and therefore extremely disturbing. She seems to be alive, you may say, and it is easy to understand what Metinides means when he compares pictures of violent death to film frames.

There are some photographs in which death is seen from the perspective of the living, the onlookers, as a mere show. A picture shows the corpse of a man floating in the water and a man swimming to retrieve him. And, reflected upside-down in the water, here they are: hundreds of men and women crowded to look at the scene, driven by morbid curiosity.

Now Metinides has retired, but he can trace back the detailed story of each picture: death is still inside him and is bound to touch anyone who looks at his pictures. The liquid eyes of Adela Legarreta are his urban chronicle, and to a certain extent also our own.