1993. Kevin Carter is a photographer. And he decides to capture one of the most complex realities in the world, his homeland. Africa. Where people die every day. So many people. In 1993 as well as today. Of starvation, wars, malaria, Ebola, AIDS. The world knows it. Sometimes it intervenes. Sometimes it doesn’t. But Kevin Carter is not like the rest of the world. He is a young Ulysses, driven by a desire for knowledge, and he flies from Johannesburg to Sudan, after his lens has already captured a lot of deaths. During the 80s, he is one of the founders of the Bang Bang Club, that immortalizes the atrocities of the Civil War in South Africa: guns held to heads, machete killings, the practice of “necklacing”, which Carter himself is the first to photograph…

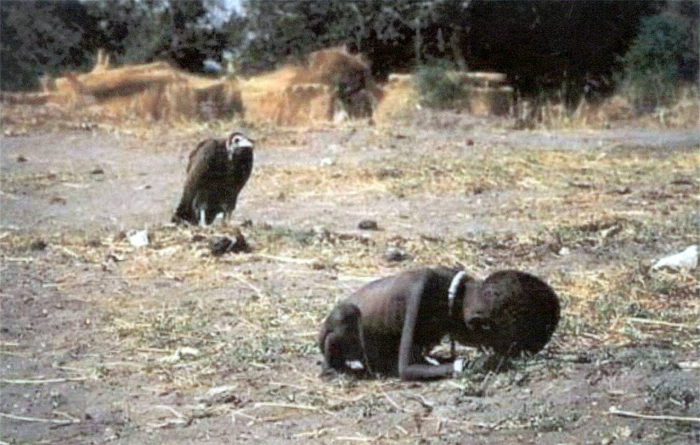

But none of his pictures is as powerful as this one: the field is completely empty, except for two figures; in the foreground a little girl cuddled up – her face buried in her hands, her impressive skinniness; not far from her a vulture patiently waiting. This picture is Africa in its wholeness: it slaps you in the face and depicts a condition that, since 1993, has changed little or nothing. Because hunger still exists and women and children are the ones who pay the highest price for it. 850 million people all over the world. Many of them are African, precisely. This picture is also Kevin’s destiny: he is awarded the Pulitzer for it but is overwhelmed with questions and criticism. What happened to the little girl? Did you save her? Why did you take a picture of her instead of helping her? What kind of man are you? Don’t you have an ounce of sensitivity?

Carter’s answer is summed up in the few lines he writes on a billet: “The pain of life overrides joy to the point that joy does not exist.” He writes these last words before committing suicide. Because the pain he has witnessed upsets him more than anyone else. The pain he has captured, disclosing it to everybody. “Nothing is more persuasive and expressive than what you see with your own eyes. You can excellently describe armed policemen attacking demonstrating workers, a worker’s body trampled on by policemen on horses or a nigger lynched by a brutal bloody torturer, but any image described in oral or written form can’t be as persuasive as a photographic reproduction. The photographer is the most objective of all drawers. He captures only what appears before his lens as he shoots. And a photographic image is intelligible in any country, to all nationalities, and even at the cinema, in spite of the language, the title and the explanations.” (Tina Modotti, Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung, Berlin 1932)

Post scriptum. Carter was unable to say what had happened to the little girl. El Mundo revealed her destiny a few years ago. The little girl was actually a little boy: his name was Kong Nyong. At that time he survived, thanks to a UN mission. But he died after four years, of fever.