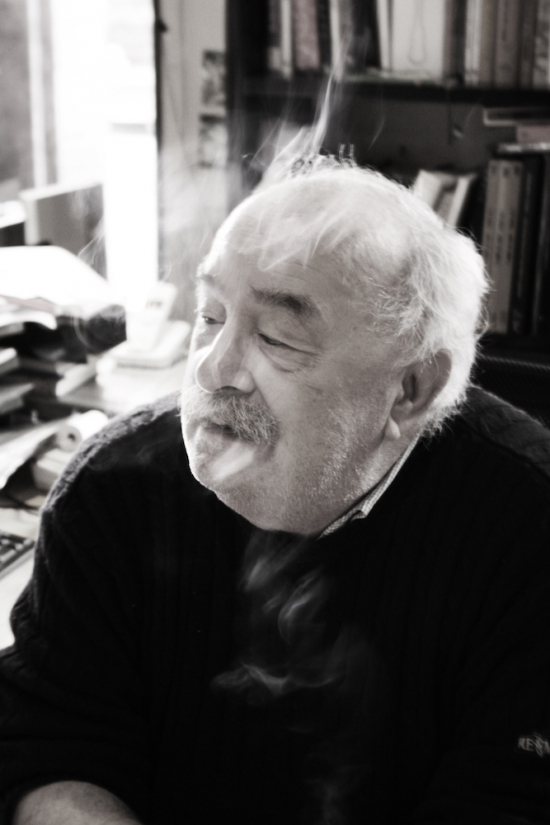

A cloud of smoke welcomes me to an art bookshop in Bologna. Shelves and shelves crammed with books. No fiction. No school books. The smoke reminds me of the time spent around books. Of bookfairs. Where you used to find ashtrays in every corner. Of the meetings between booksellers and publishers, all having a cigarette in their mouth. As if words should necessarily pass through tiny teeth yellowed by tobacco. Books and tobacco. Maybe it has something to do with the act of quietly breathing smoke in and out. And ideas. Beyond the smoke two lively eyes are wondering who I am and what I want. Fabio Paltrinieri. The bookseller and owner of the art bookshop IL LEONARDO. He smokes MS cigarettes. He looks at me from behind the table. He has been working as a bookseller since he was about 30 – “after having pretended to study architecture in Florence for 10 years” he says. In the 70s he came back to Bologna and matriculated at the new faculty of DAMS, to stay close to his family in Finale Emilia. To earn his living, he looked for a job at music shops and bookshops, two things he loved. He was employed by Nanni, one of the first remainders in Italy, where Carmine, a true institution, taught him everything about books, especially art books. He shows me the picture of Carmine that he keeps safe on his desk. In front of him. He never managed to attend DAMS but after 12 years working at Nanni’s, he opened his own small bookshop in via Porta Nuova, specialising in art, cinema and music, which was soon entirely consecrated to art. He worked there for ten years before moving to his present-day shop in via Guerrazzi. He smiles and remembers the great art historian Federico Zeri, who – when he learnt Fabio was moving to a bigger shop – told him “It’s not size that matters, but the brain of the people inside” and mentioned St George’s bookshop in London which – small as it was – “had served half the world.”

Paltrinieri is alone in the bookshop. He used to have an assistant but he had to cut the expenses because of the crisis. Libraries and faculty departments have run out of funds. They used to buy books in the past, but nowadays they don’t do it anymore or they buy them directly from the publishers.

This is why our bookseller had to learn how to use computers and e-mails… “Since I want to die here, I want to keep the bookshop open as long as possible. In the meantime I have learnt to do everything. Needs made me sharp and pragmatic.” He has always been sharp, I believe. Conversation with him is charming. Time goes by among the memories of his bookshop, like eyes browsing the pages of a book.

A young man comes in, maybe a professor. He asks for a book. Paltrinieri knows exactly where to find it and shows him without even getting up from his chair. The man leafs through the book. He shuts it. He puts it near the cash till. But he wants something more. He is looking for information and looks trustful at his bookseller. He knows he is going to tell him exactly what editions he needs. They exist. He can get them. Where that work is. And if it is represented in the catalogue he is submitting. He has customers from every part of the world. Professors to whom he writes e-mails to keep them updated about a given issue of their interest. Always a rather specialist interest. “There is a professor in Japan” he tells me “specializing in 17th Century Art in Bologna” he looks at me attentively and takes the opportunity for brushing me up on that art period. The customer is still motionless near the cash till. He says he wants to pay for the book and takes the opportunity to have a chat. He needs to discuss his passion with somebody. To be understood. He needs some information about how and where he should go to find his love. And our bookseller pleases him. Serious.

We make a small tour. We see other things. He opens drawers. And I ask him to whom he is going to leave the bookshop in the future. He smiles. He always smiles. “To nobody. I already told you I want to die here.” He points at a place in the room and goes on “I will put a bed right here and lock myself inside.” I will come back and visit him. To see him arrive on his bicycle. I will ask him if I can sit down and have a morning coffee with him.

“I get dressed very quickly each morning, I take my bike and have a coffee right beside here.”

Looking at his bookshop. I think.