It is difficult to go back to the precise moment when the Western man started to distinguish Culture from Nature and to perceive a gap between his own world (regulated by social norms) and the one he considers to be the outside world (governed by more imponderable laws).

We certainly still feel this separation today, as if we didn’t really belong to what we call Nature. We have erected square buildings which contrast with its curved and fluid shapes and then we have convinced ourselves that our towns are something more than nests and dens; we have attributed superior qualities to our behaviours, going as far as to be afraid that human beings could finally “destroy Nature”. And we paradoxically feel nostalgia for a supposed lost communion with animals, plants, etc. Some people end up bearing the costs of this view of the world. One of them was Timothy Treadwell, the protagonist of Grizzly Man, the brilliant documentary film by Werner Herzog: as he tried to “communicate with bears”, he was torn to pieces and so was his partner.

Tippi Degré is a quite different example, which nevertheless encourages reflection. Born in Namibia in 1990 of French parents dealing with photographic services in the savannah, little Tippi lived for ten years in the so-called “unpolluted nature”. Endowed with an outstanding charisma, great energy and an absolute lack of fear in front of animals, this little girl spent her days in harness with them from an early age. As she hadn’t the possibility of meeting other children, animals became her only friends.

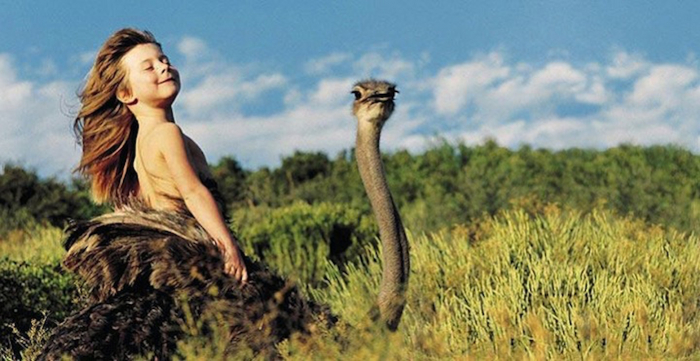

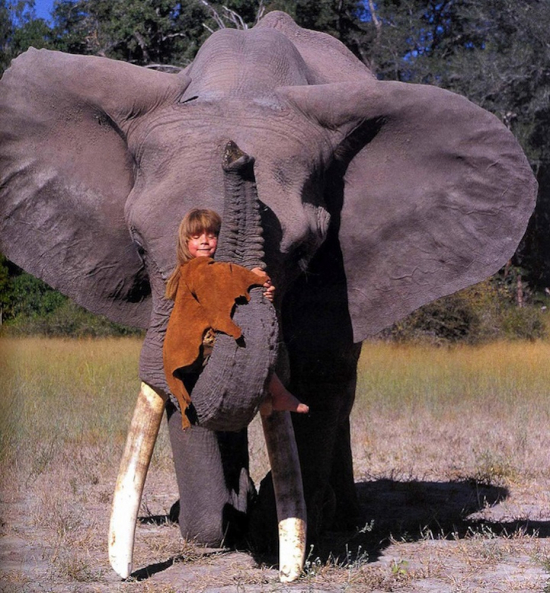

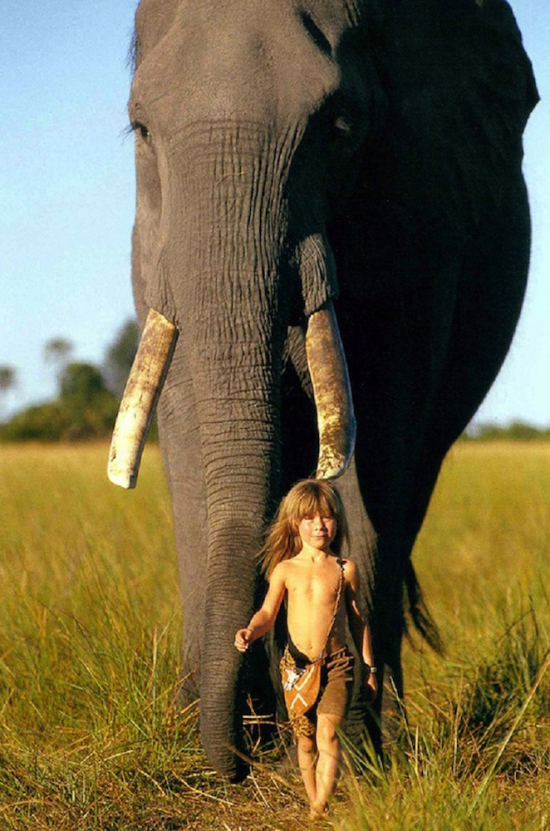

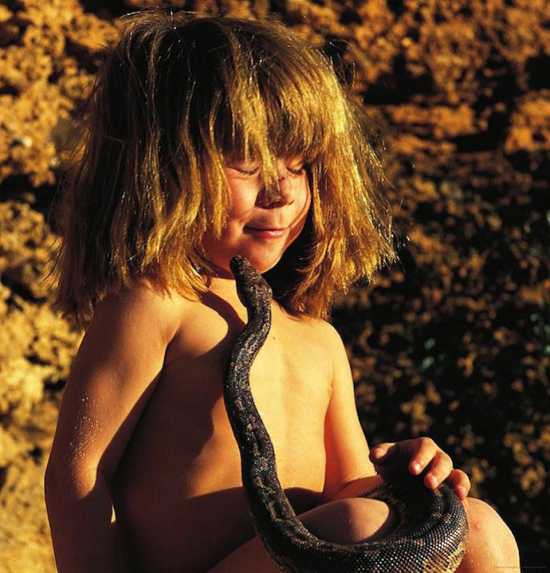

Tippi is the protagonist of photographs and documentaries made by her parents where she plays and “communicates” in an extraordinary and moving manner with Abu, a 28-year-old elephant, with a leopard called J&B, with Linda, the ostrich that has been looking after her like a mother, and with a variety of other animals: crocodiles, mongooses, zebras, snakes, chameleons, giraffes, lions, and many more. The self-confident little girl knows how to behave, and immediately understands which is the limit she shouldn’t exceed, always aware of what animals do like and what annoys them. So she proves fearless in front of a leopard, because “it must know that I can fight, otherwise it’ll eat me”, and she rides orchids and elephants without problems.

But the Degrés were not irresponsible parents. The wild beasts we see in the pictures had been brought up by human beings since their birth, they were accustomed to their presence and well-fed, therefore we can say Tippi didn’t quite run any real risk. The pachyderm Abu, her best friend, had a long career behind it as an “actor” playing in Disney Movies.

When her family returned to Paris in 2000, Tippi immediately became an international star thanks to photographic books and documentaries. People are moved and fascinated by her story, because the little girl was turned into a symbol – a bridge between Culture and Nature. By virtue of her innocence, Tippi seemed able to get in tune with dangerous and wild beasts: a harmony that is remindful of Saint Francis of Assisi, or Kipling’s little Mowgli.

Reality, we know, is different, because, if the leopard had really been wild, the little girl wouldn’t even have had the time to approach it. We don’t want to be accused of exaggerated cynicism, which would spoil the effect of these wonderfully shot pictures: on the contrary, we think that, in addition to the evocative and undoubtedly discharging power of the pictures, there is a further level of meaning, one that makes us plunge into deeper issues. Why are we moved by such scenes? What is it that really draws us away from Nature? Furthermore: can we really love Nature without accepting its massacres as well?

Human beings have always needed some kind of fairy-tales, and maybe the story of Tippi satisfies this need with child’s sweetness and charm.