MEMORY - Part 2

by Lina Vergara Huilcamán, Sonia Maria Luce Possentini

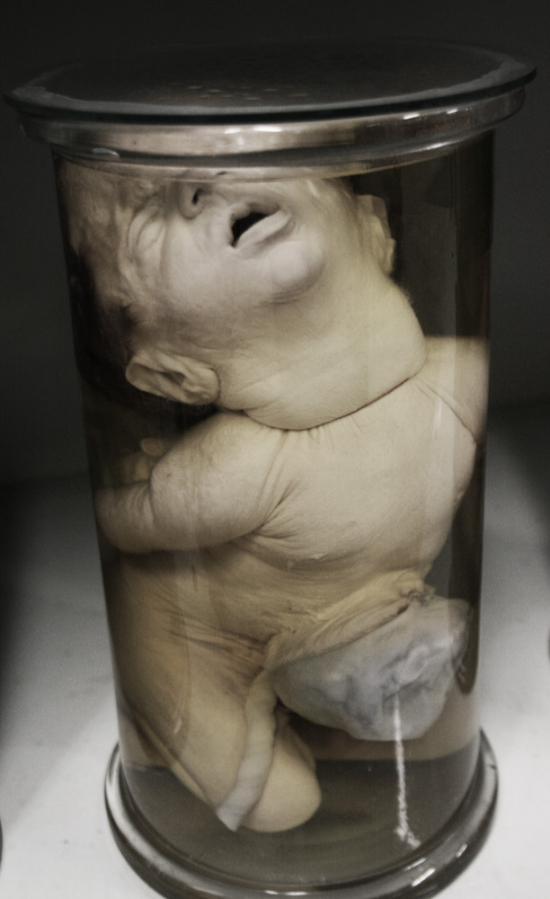

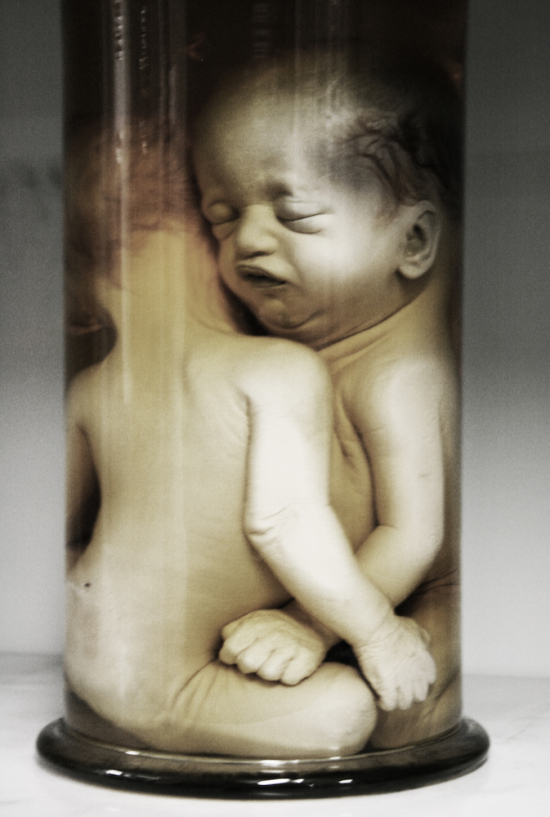

A cold morning at the end of January saw us visit the Museo Morgagni in Padova. Dr. Alberto Zanatta welcomed us and with great passion opened the museum displays to show us – but above all to explain us – the pieces of the collection. The teratological preparations, which we are going to illustrate here, can arouse disgust. Most people think it is a sign of slightly macabre taste to look at these little human beings in glass and watch their malformations, especially if you are not a doctor. To see with your eyes a couple of Siamese twins, an anencephalous (lacking in cranial vault and encephalon), a foot with six fingers, or a monops. But this is nature. Sometimes we find it lovely, sometimes it looks weird, bizarre and “monstruous”, to use a popular term.

(In a broad sense, a monster is a living being – real or fictitious – which is believed to have one or more extraordinary features, that make it extremely different from other beings regarded as normal, “ordinary”. In general, the word monster has a negative connotation. The word itself – from the Latin term monstrum, from monere – means “wonder”, “prodigy”, and can take on ambivalent nuances.) (1)

The human body has always aroused my curiosity. When you have the chance to look at it while a person like Dr. Zanatta explains its pathologies, an unlimited world opens up before your eyes.

I saw it in the eyes of my daughter who visited the museum with us.

Why Monster? Why fear? Why disgust?

It’s nature. A little chance that can occur to any of us.

You understand it as you look at the faces of those children inside glass jars, immersed in the liquid that preserves them, children that retain the same frailty and expression of any living child we keep in our arms. I think we become more human when we look at them. More aware of our body and our flesh. I find the insanity of our cells or of our genetic heritage fascinating. And I am also fascinated by knowledge, by the visual experience of anything that concerns our human nature. Its extraordinariness, to quote the definition of the monster.

Every single one of us should nourish and develop their ability to understand, think and imagine, in order to limit the space of the unknown and therefore of fear and intolerance.

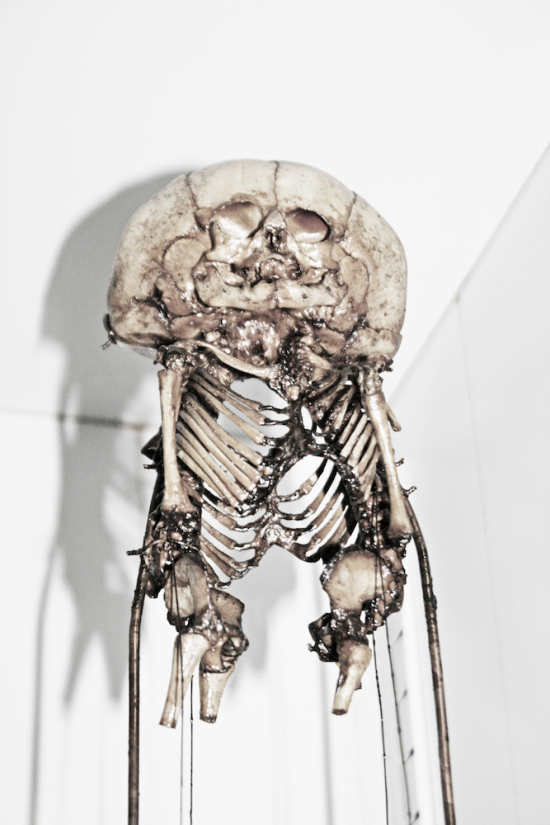

I had a nice experience at the Museo Morgagni, and I hope it will soon be open to the public. Especially because, apart from the teratological preparations of Siamese twins, for example, it shows you their skeleton, the bone malformations due to various diseases, the devastation provoked by syphilis. It allows you to admire a masterpiece of tannization by Brunetti (2): The Punished Suicide (3), which proves that medicine can be turned into art and meaning, a masterpiece that won its author a prize at the Exposition Internationale de Paris in 1867.

The Museo Morgagni is located in the Anatomopathology Institution of the University of Padova. It has mainly an educational function and can be visited by agreement with the person in charge. There are more than 1500 specimens, divided according to pathology or preservative method: tannization, waxification, mummification. You can see individuals with rare deformities due to various diseases: monops, thoracopagus twins, lepers, people suffering from argyrosis. (4)

The University of Padova, founded in 1222, is one of the most ancient universities in Europe. By virtue of this long history, the richness of its Science Collections and museums and the amount of documents and books kept in its ancient Libraries are surprising, although they are almost completely unknown to the majority of citizens. This is the reason why during the last years the University of Padova has pursued an organic policy for the enhancement of this heritage, being aware of the fact that it doesn’t simply belong to the university but to the whole humankind.

The University’s Museums, Science Collections and Libraries are located inside the deparments to which they belong, in various areas of the town.

Interesting links

(1) en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monster

(2) musme.padova.it/collezioni-tannizzazione.aspx

(3) musme.padova.it/reperti-scheda.aspx?id=c3ccc658-f298-47d0-96bd-2a64a21c5422

(4) museo-morgagni.blogspot.it